Reframing Obesity: What ‘Enough’ Gets Right — and Where the Conversation Should Grow

As I enter the clinic more and more during my 3rd year of medical school, I’m seeing something new and consistent: patients are asking about GLP-1 medications.

Some are curious.

Some are hopeful.

Some are frustrated.

And some are already taking them — sometimes adjusting doses on their own because they want faster results.

When science, media, and patient behavior intersect this quickly, it’s worth slowing down and looking at the full picture. My goal here is simply to think out loud about what I’m seeing in clinic, share information from my training, and reflect on the broader conversation sparked by the book Enough: Your Health, Your Weight, and What It's Like To Be Free by Oprah Winfrey and Ania Jastreboff M.D. Ph.D.

Because this conversation matters!

What I Appreciate About ‘Enough’

There is a lot to like about the book.

It shifts the tone around obesity.

One of the most important contributions of Enough is its emphasis on reducing shame.

For decades, people with obesity have been blamed, dismissed, or treated as morally deficient. The book pushes back on that narrative and invites both clinicians and patients to reconsider the language we use. This aligns closely with Brené Brown’s PhD work on shame — shame rarely creates lasting change. Compassion does.

That cultural shift is long overdue in our society, but especially in certain aspects of medicine/health.

This shift away from shame also echoes themes from the Health at Every Size (HAES) movement, which emphasizes respectful care, behavior-based health improvements, and reducing weight stigma. While perspectives differ on the role of intentional weight loss, the shared goal of compassionate, patient-centered care is important.

It explains the science behind GLP-1 medications.

The book accessibly walks readers through the evolution of GLP-1 medications — from research to clinical application. It explains hunger hormones, satiety signals, and why weight loss can be biologically difficult.

For patients who feel like they’ve “failed,” this explanation can be validating.

It challenges our reliance on BMI and the scale.

BMI is imperfect. So is the number on the scale.

An athlete with higher muscle mass (e.g., Arnold-Schwarzenegger) would technically qualify as “overweight” or “obese” by BMI standards despite extremely low body fat. Weight alone does not equal health.

The book encourages us to look beyond one number — and that’s an important message.

It emphasizes reframing and small change.

There are themes in the book that align with ideas from Atomic Habits — small, sustainable, incremental changes matter. SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, Time-bound) are more effective than dramatic overhauls.

That approach works in medicine. And in life.

It highlights a critical safety issue: more is not better.

In clinic, we are seeing patients increase their own GLP-1 doses because they want faster results.

But aggressive weight loss is not healthy, nor sustainable in the long run. Losing more than 1–2 pounds per week increases risk of:

Muscle loss

Nutrient deficiencies

Gallstones

Metabolic stress

GLP-1 dosing safety: Self-dosing is not safe! More medication does not equal better health. You wouldn’t self-adjust your blood pressure medication or birth control. Same logic applies to GLP-1 medications.

Where I Think the Conversation Could Expand

Here is where I think we need more nuance.

Obesity as a “disease” — but not the whole story.

The book strongly frames obesity as a chronic disease driven by biology.

There is truth here — appetite regulation, genetics, and hormonal signaling absolutely matter.

But we also know something else:

Approximately a quarter to nearly half of American adults did not develop a novel biological disease in just two to three generations. Our physiology does not adapt to such a deep process that quickly.

What changed?

Food systems: food deserts, food inequality, socioeconomics

Easy access to Ultra-processed foods that are addictive, nutrient poor, trigger inflammation

Sedentary work: sitting is the new smoking

Sleep patterns:

Chronic stress: emotional state signals physiological changes (take breathing for example)

Growing portion sizes

Social norms

Obesity is biological — but it is also environmental and behavioral. It is cumulative and interactive. When we focus heavily on disease and medication, we risk under-emphasizing these drivers. When obesity is framed exclusively as a biological disease, there’s a subtle risk of minimizing the role of daily behaviors and environment — and with that, the sense of personal agency we may have in shaping our health.

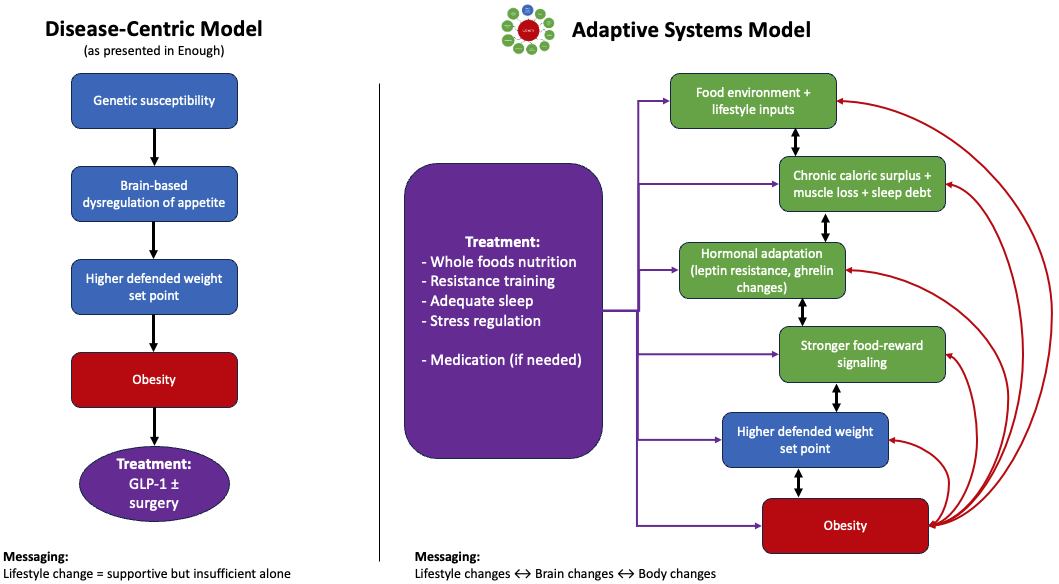

To make this idea more concrete, here’s a simple way to visualize this complex system of biology, environment, and behavior:

When we talk about obesity as a disease, it can unintentionally make it seem like the brain is the sole driver. But studies have shown obesity is the result of many factors and these all interact with each other further compounding the effects.

The question then becomes: how do we organize this complexity?

One way is to frame obesity primarily as a brain-based disease with downstream effects. Another is to view it as a complex adaptive system — where environment, behavior, and biology continuously influence one another.

Here’s how I interpreted the model presented in ‘Enough’ compared to a more whole-body, adaptive systems way of thinking:

The distinction is not whether biology matters — but how we organize cause, adaptation, and treatment.

Both models acknowledge brain regulation and hormonal adaptation. The difference lies in emphasis. The disease-centric model locates the primary driver in brain dysregulation. The adaptive systems-based model suggests that brain regulation adapts in response to repeated lifestyle and environmental inputs.

2. Transparency and financial disclosures.

In clinical research, conflict-of-interest disclosures are required. This is an ethical safeguard.

Most general health books, podcasts, and influencers do not clearly explain these relationships — even when they exist.

This is not an accusation. Collaboration between researchers and pharmaceutical companies is common and often necessary. But readers deserve transparency.

For example, here is mine:

I am a 3rd year medical student (at the time of this writing). I am not a physician (yet), and this post is not medical advice.

I have no financial ties to pharmaceutical companies.

I receive no compensation related to GLP-1 medications or any other pharmaceuticals.

This blog does not generate any financial income (e.g., no affiliate links).

I think we (clinicians and the public) should normalize the same level of clarity in public health conversations, just as we do in medical research.

3. Our medical “Mary Poppins bag” is has so many tools from which we can use!

Medication and surgery are two such tools. Powerful ones. But they are not our only tools.

In clinic, I see patients who have amazing health changes and benefits from the cumulative power of:

Sleep optimization

Resistance training

Protein adequacy

Sufficient hydration

Stress regulation

Ultra-processed food reduction

Fiber and whole-food intake

Behavior change frameworks

When layered together, these can rival — and sometimes exceed — medication in long-term impact. The most sustainable outcomes I’ve seen are not medication-only. They are integrated approaches.

Researchers like Stacy Sims, PhD, have also helped raise awareness about the unique metabolic and hormonal shifts women experience — particularly in midlife — and how targeted strength training, protein intake, and recovery strategies can meaningfully influence body composition and health. That work reinforces the idea that biology and lifestyle are not opposing forces — they are interactive.

Five Actionable Takeaways

Here are five practical steps anyone can start with:

1. Use SMART goals for weight loss and health.

Instead of “I’m going to get healthy,” try:

“I will walk 20 minutes after dinner 4 days per week.”

“I will add one serving of vegetables at lunch.”

“I will do 5 minutes of breathing (meditation/mindfulness) 3 days this week before going to bed.”

Small wins compound. (Atomic Habits principle.)

2. Aim for sustainable weight loss.

If you are losing weight, 1–2 pounds per week is generally considered safe. Faster is not better.

Protect muscle. Protect metabolism. Protect long-term health.

3. Focus on behaviors, not just the scale.

Better things to Track:

Strength gains

Energy levels

Sleep quality

Blood markers

Endurance

Like each individual, your health is multidimensional… don’t reduce it down to only a few measures.

4. Shift language away from shame.

Whether you are a clinician, family member, friend, or coworker… words matter. Your internal self-dialog matters.

Shame shuts people down.

Curiosity opens them up.

Brené Brown’s research is clear on this - no wonder her TED talks are some of the top watched of all time.

5. Practice critical thinking in health media.

When you read a health book, watch an interview, or listen to a podcast:

Who funded the research?

Are limitations discussed?

Are alternative viewpoints presented?

What happens long-term?

What happens when treatment stops?

Listen to opposing opinions. Medicine advances through healthy, constructive tension and debate.

Final Thoughts

GLP-1 medications are not villains. They are also not magic. Clinician’s go through years of intense training to know how to select the appropriate tool(s) for each individual patient’s health goals and how to safely and effectively use those tools.

Obesity is not purely a moral failure. It is also not purely a disease divorced from environment and behavior.

The truth — as it often is in medicine — lives in the integration.

And as I move through clinic in training, what I’m learning most is this:

The most powerful tool we have isn’t a medication. It’s the ability to educate, individualize, and build sustainable change with patients — not for them.